I

Aurel I. Rogojan

În prima zi a lunii decembrie 1989, cu o zi înaintea întâlnirii cu președintele american George Herbert Walter Bush de la Malta, liderul sovietic Mihail Sergheevici Gorbaciov a avut o convorbire de 76 de minute cu Papa Ioan Paul al II-lea, durata audienței fiind apreciată ca extraordinară, ceea ce a stârnit și curiozități pe măsură în legătură cu problemele abordate. La un deceniu după întâlnire, New Catolic Service a făcut publică o parte a transcriptului convorbirii, cea a abordărilor generale, de neevitat, potrivit uzanțelor protocolare ale întâlnirilor la acest nivel: situația internațională, libertatea cultelor în Uniunea Sovietică.

Celălalt finalist din cursa Războiului Rece, George Herbert Walter Bush a avut audiența la Vatican pe data de 27 mai 1989. Interesant este ce a urmat acestei audiențe. Imediat după convorbirile avute cu Papa Ioan Paul al II-lea, președintele american s-a întâlnit cu cancelarul vest-german Helmuth Kohl, iar la Mainz a ținut un discurs prin care a anticipat agenda Conferinței de la Malta. În continuare, G.H.W. Bush s-a deplasat la Londra, iar în prima jumătate a lunii iulie la Varșovia, Gdansk și Budapesta.

„Miracolul” Wojtyla și Gorbaciov

Semnificațiile auspiciilor papale au fost rezumate de secretarul pentru Afaceri Externe al Vaticanului, cardinalul Agostino Casaroli, cu prilejul conferirii titlului de Doctor Honoris Causa al Universității din Cracovia, când a spus: „Miracolul rapidelor schimbări din Europa de Est poartă numele a două personalități fundamentale, Wojtyla și Gorbaciov („La Republica.it, 03 iunie 1990, „Miracolo all est grazie a Gorbaciov e Papa Wojtyla”). Și necesara completare lămuritoare: „Alla vigilia del vertice tra Gorbaciov e il presidente degli Stati Uniti d’America, George Bush, Wojtyla auspica che i prossimi colloqui possano portare a nuove intese, ispirate ad attento ascolto delle esigenze e delle attese dei popoli”.

Neîndoielnic, cei doi lideri și-au legat unele dintre angajamentele convenite în fața Papei Ioan Paul al II-lea, căci ulterior tot ceea ce a fost binecuvântat la Vatican a avut prioritate absolută. Vom reveni asupra consecințelor audiențelor papale.

În zilele de 2 și 3 decembrie 1989, Uniunea Sovietică a găzduit pe teritoriul său, reprezentat de crucișătorul Maxim Gorki ancorat în Golful Marsaxlokk, din portul orășelului maltez cu același nume, ceea ce istoria consemnează drept „Întâlnirea de la Malta”.

„Sfârşitul Războiului Rece”

Despre „Întâlnirea de la Malta”, M.S. Gorbaciov a spus, în cea mai pură expresie a jargonului kremlinez, că a reprezentat „o cotitură istorică”. Semnificația formală cotiturii istorice, cea destinată viitorimii, a fost dăltuită, în limbile malteză, engleză și rusă, în piatra nobilă a plăcii Monumentului Bush/Gorbachev cold war Memorial ridicat pe faleza orăşelului Birzebbuga (cca. 8 kilometri de capitala La Valleta): „Malta 2–3 decembrie 1989, George Bush, Michael Gorbachev” „Sfârşitul Războiului Rece”.

La momentul întâlnirii, M.S. Gorbaciov își îndeplinise în proporție de 75% angajamentul prealabil privind înlăturarea de la putere a ultimilor patru lideri comuniști rămași pe poziții împotriva valului. Generalii din sistemele de putere secretă ale R.D. Germană, Cehoslovaciei și Bulgariei la care directorul K.G.B.-ului, Vladimir Kriucikov, a făcut apel pentru scoaterea din conservare a opozanților lui Erich Honeker, Gustav Husak și Todor Jivkov s-au dovedit eficienți și loiali Moscovei.

Generalii Moscovei de la București, marionete naive

Generalii Moscovei de la București, marionete naive ale unor tentative anterioare de puciuri de operetă, lamentabil eșuate, nu mai aveau conexiunile și nici credibilitatea necesare.

II

Aurel I. Rogojan

La momentul întâlnirii, M.S. Gorbaciov își îndeplinise în proporție de 75% angajamentul prealabil privind înlăturarea de la putere a ultimilor patru lideri comuniști rămași pe poziții împotriva valului.

Generalii din sistemele de putere secretă ale R.D. Germană, Cehoslovaciei și Bulgariei la care directorul K.G.B.-ului, Vladimir Kriucikov, a făcut apel pentru scoaterea din conservare a opozanților lui Erich Honeker, Gustav Husak și Todor Jivkov, s-au dovedit eficienți și loiali Moscovei.

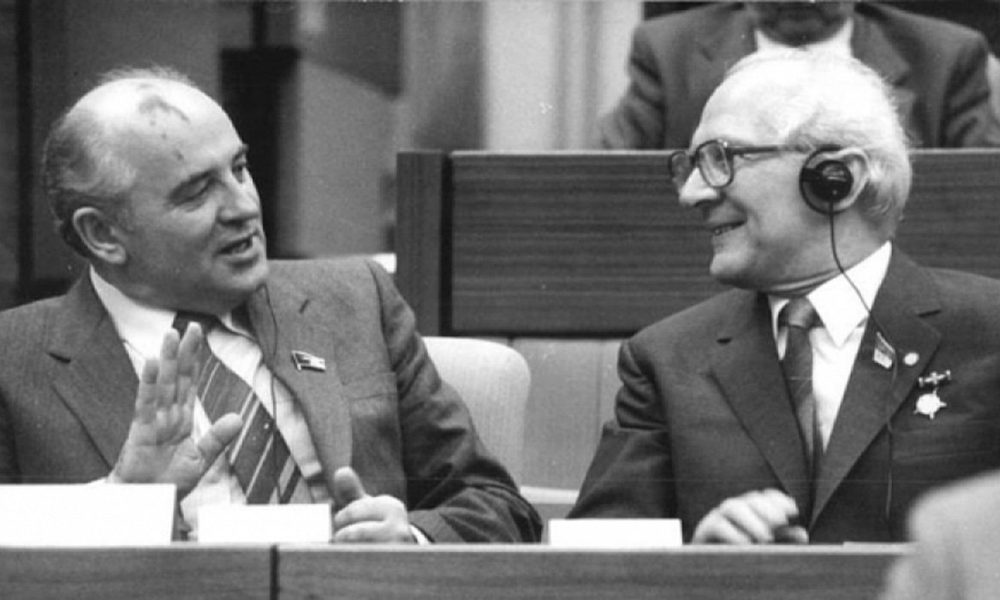

Şeful KGB l-a debarcat pe Erich Honecker

Rezidentul-șef al KGB-ului în Germania de Est, generalul Ivan Nikolaevici Kuzmin, în calitate de martor ocular al evenimentelor petrecute în Republica Democrată Germană în anul 1989, arată că anterior vizitei lui Gorbaciov în această țară, prilejuită de aniversarea a 40 de ani de la înființarea statului est-german, rezidența trebuia să pună la dispoziția Moscovei două documente: „Informare operativă asupra situației din conducerea Partidului Socialist Unit German“ și „Sinteza privind starea de spirit din Partidului Socialist Unit German“. Din ambele documente, fără a se recomanda expres, fiindcă KGB-ului nu-i era permis să se amestece în procesul deciziilor politice, rezultă necesitatea demiterii secretarului general Honecker din toate funcțiile de partid și de stat.

Premierul Willi Stoph și Erich Mielke, șeful STASI, dar și altii, l-au rugat pe Gorbaciov să-i sprijine în opoziția lor față de Honecker. Rugămintea acestora era, de fapt, corolarul celor două rapoarte ale K.G.B.-ului. Gorbaciov nu le-a răspuns. Vladimir Kriucikov și-a asumat personal înlăturarea lui Honecker, iar cine trebuia i-a tălmăcit lui Willi Stoph ce semnifică tăcerea în astfel de împrejurări, adică acord fără rezerve.

La 17 octombrie, Erich Mielke, șeful STASI, a propus Biroului Politic eliberarea lui Honecker din toate funcțiile deținute, ceea ce s-a acceptat imediat. A doua zi, noul secretar general era Egon Krenz, fost secretar al Comitetului Central și șef al Secției C.C. al P.S.U.G. pentru armată, interne, securitate, procuratură și justiție. I-au succedat, la scurt timp, Hans Modrow și Gregor Gyusi.

Iluziile Moscovei

11.03.1985 este data la care agentul schimbării, Mihail Sergheevici Gorbaciov, și-a intrat în rol și niciun alt lider est-european nu a mai contat.

Faptul că Honecker a fost schimbat ca urmare a dorinței lui Gorbaciov este fără echivoc exprimat de ambasadorul de atunci la Bonn al URSS, Kwitinski, care ulterior a afirmat: „Moscova și-a făcut iluzii că era suficient să-l înlocuiască pe Honecker și totul va fi în regulă…”.

Gorbaciov – în discuțiile cu Egon Krenz, iar mai apoi cu succesorul acestuia, Gregor Gysi – împărtășea un optimism exagerat, ca și cum nu ar fi primit și nu ar fi citit informațiile transmise de rezidența KGB din Berlinul de Est și, în fapt, de aparatul împuternicit al KGB-ului din RDG (din care făcea parte și Vladimir Putin).

Aparenta surprindere a lui Gorbaciov

Evenimentele ulterioare, respectiv căderea zidului Berlinului, i-ar fi surprins atât pe Gorbaciov, cât și KGB-ul. În următoarele 3–4 zile, rezidența KGB a pregătit o evaluare și o prognosticare a situației, raportul fiind transmis în seara zilei de 13 octombrie 1989. Evaluarea nu a fost acceptată, fiind clasată cu rezoluția „excesiv defetistă“. Peste șase zile, când s-a cerut un nou raport, evenimentele depășiseră și cele mai sumbre previziuni. În locul Ministerului Securității Statului, Camera Populară a RDG a înființat Oficiul pentru Securitatea Națională, iar la 3 decembrie, o nouă surpriză, înlăturarea lui Egon Krenz, a semnificat falimentul politicii reformatoare, așa cum fusese gândită de Gorbaciov.

Centrul KGB de la Karhorst și-a încetat, în cursul lunii decembrie, activitatea de legătură cu serviciile locale. Documentele operative și de informații au fost inventariate și trimise la Moscova, iar celelalte distruse pe loc.

Amplă operaţiune sub drapel străin a KGB-ului

Cum s-a ajuns în această situație, aproape pe neașteptate? În realitate, scenariul evenimentelor din R.D. Germană, în mod special, precum și evoluțiile care s-au girat prin gentlemen’s agreementul de la Malta au fost anticipate și puse în operă la ordinul lui Iuri Vladimirovici Andropov, fost director al KGB (1967-1982), secretar general al PCUS (1982-1983). Andropov a inițiat o amplă operațiune clandestină sub steaguri străine, cunoscută doar de trei persoane din Departamentul Ilegali al KBG, cu scopul de a se putea prelua sub control alternativele la regimurile totalitare comuniste.

Stricta compartimentare a operațiunii a facilitat autonomizarea nucleelor operaționale, acestea acționând independent, cu autofinanțare și fără legături cu Moscova, care depistate ar fi putut compromite scopul urmărit. Aceasta a fost partea clandestină a schimbării în care și Gorbaciov a avut un rol, considerat de el și de istorici ca fiind misiunea unuia dintre giganții secolului al XX-lea, care au schimbat lumea.

Pentru scenariștii și regizorii din umbra evenimentelor, toți actorii acestora au fost exact ceea ce era trebuincios schimbării direcției date istoriei prin experimentul revoluționar din anul 1917, brutal extins în anul 1945, în numele victoriei asupra nazismului, până în inima Europei, cu permanente pericole pentru ordinea democratică occidentală din Spania, Portugalia, Italia, Franța.

Ulterior, în anii ‚70, Moscova a devenit influentă în Somalia, Etiopia, Cambogia, Vietnam, Mozambic, Angola, Laos, Afghanistan.

Nimic nu a fost neplanificat în 1989

Agentul schimbării, Mihail Sergheevici Gorbaciov, și-a intrat în rol la 11 martie 1985, dată de la care niciun alt lider est-european nu a mai contat.

Începând cu anul 1989, emisari ai lui Gorbaciov – îndeosebi șeful KGB, Vladimir Kriucikov, dar și alții cu legături ori antecedente în KGB – au trecut la scoaterea din conservare a unei rețele, până atunci pasivă, de opozanți ai liderilor de partid și de stat aflați la putere în țările socialiste central și est-europene, fiind stabilit modul în care aceștia vor asigura transferul puterii către așa-zișii reformiști.

Schimbarea lui Erich Honecker a fost rezervată lui Vladimir Kriucikov. Acesta din urmă a efectuat cel puțin trei călătorii în Germania de Est, din care una secretă, pentru a putea avea convorbiri cu reprezentanți ai „opoziției“, printre care și cu profesorul Manfred von Ardenne.

Amploarea manifestațiilor declanșate imediat după ce Gorbaciov și ceilalți lideri comuniști est-europeni au părăsit Germania de Est, unde participaseră la cea de-a 40-a aniversare a creării RDG-ului, a creat climatul propice înlăturării lui Honecker. Numai că în locul lui nu a venit, așa cum era așteptat, reformatorul Hans Modrow, ci Egon Krenz, omul KGB-ului, susținut de Kriucikov. Egon Krenz pare să fi fost însă depășit și speriat de evenimente, scăpând situația de sub control. Deciziile sale, luate fără a se mai consulta cu Moscova, l-au surprins, chipurile, și pe Gorbaciov. Nimic nu a fost însă neplanificat, ori fără pachetul complet al soluțiilor alternative.

În realitate, scenariul evenimentelor din R.D. Germană, în mod special, precum și evoluțiile care s-au girat prin gentlemen’s agreementul de la Malta au fost anticipate și puse în operă la ordinul lui Iuri Vladimirovici Andropov, fost director al KGB și secretar general al PCUS.

III

Aurel I. Rogojan

În

zilele de 2 și 3 decembrie 1989, Uniunea Sovietică a găzduit pe

teritoriul său, reprezentat de crucișătorul Maxim Gorki ancorat în

Golful Marsaxlokk, din portul orășelului maltez cu același nume, ceea ce

istoria consemnează drept „Întâlnirea de la Malta“. Despre „Întâlnirea

de la Malta“ cu președintele George H.W. Bush, M.S. Gorbaciov a spus, în

cea mai pură expresie a jargonului kremlinez, că a reprezentat „o

cotitură istorică“.

La momentul întâlnirii, M.S. Gorbaciov își îndeplinise în proporție de 75% angajamentul prealabil privind înlăturarea de la putere a ultimilor patru lideri comuniști rămași pe poziții împotriva valului.

Moscova, refuzată de protagoniștii „Primăverii de la Praga“

În Cehoslovacia, ramura locală a KGB-ului din cadrul Securității Statului – STB – a încercat readucerea în actualitate a unora dintre protagoniștii „Primăverii de la Praga“, brutal reprimată de intervenția militară a Forțelor Armate ale tratatului de la Varșovia (fără participarea României). Alexander Dubcek și fostul său ministru Zdenek Mlynar au fost contactați la Viena, dar aceștia, sub amintirea încă vie a evenimentelor din august 1968, refuză orice angajament. Alții însă se vor constitui într-un grup care s-a grăbit să ajungă la Moscova pentru convorbiri cu Mihail Gorbaciov. Acesta îi expediază repede la… KGB! KGB-ul îi pune la dispoziția șefului STB, generalul Alois Lorenc.

Ca și lui Todor Jivkov, şi lui Nicolae Ceauşescu i-a fost adresată, în luna martie 1989, o scrisoare deschisă în care, printre alte grave acuze, i se imputa prăbuşirea economică a României. Nu poate fi chiar o coincidenţă întâmplătoare…

„Turiștii sovietici“ din Cehoslovacia

În preajma zilei de 17 noiembrie 1989, la Praga au sosit, cu câteva avioane, „trupe profesioniste de revoluționari“, adică turiști sovietici din formațiunile „SPETSNAZ“ ale GRU, care s-au amestecat printre demonstranți. Un locotenent al STB, Ludek Zvicak, a fost infiltrat între demonstranți sub identitatea tânărului praghez Martin Smid, în ipostaza de element provocator, care să atace baricadele miliției. A fost împușcat… Vestea morții lui Smid face ocolul lumii, iar mulțimile stârnite nu mai părăsesc străzile. „Turiștii“ sovietici au plecat fără să mai aștepte deznodământul final.

Reporterii occidentali se înființează la domiciliul lui Smid, iar acesta apare acasă viu și nevătămat. Prea târziu însă. Efectul scontat al diversiunii se împlinise. Revoluția învinsese. Un general trimis de Kriucikov, de la Moscova, Viktor Gruskov, generalul Teslenko, șeful antenei KGB de la Praga, și generalul Alois Lorenc au supravegheat întreaga desfășurare a evenimentelor.

„Revoluția de catifea“, declanșată de KGB

Președintele Havel a afirmat categoric că „Revoluția de catifea“ de la Praga, din 17 noiembrie 1989, a fost declanșată de KGB. Havel a definit această operațiune drept „un complot pentru abolirea regimului comunist“, condus de brejnevistul Gustav Husak. Complotiștii, potrivit lui Havel, s-au folosit de protestele studenților pentru a ridica noul regim în șa și pentru a realiza reforma de tip gorbaciovist.

Tot Havel a mai dezvăluit că, inițial, s-a dorit aducerea la putere a unui membru al cabinetului Dubcek (din 1968), aflat în exil la Viena, dar acesta a declinat oferta. Mărturisirea lui Havel de la BBC a fost apoi reluată, în rezumat, și în Die Welt, fiind susținută ulterior și prin alte dovezi.

Generalul Alois Lorenc vizitase anterior Moscova, unde a fost pregătit pentru viitoarele evenimente, iar generalul Viktor Grușko a adus cu sine comandouri Spetznaz ale GRU. Ofițerii Spetznaz, care de la aeroportul Ruzine se împrăștiaseră în toată Praga, conform planului, l-au ținut permanent la curent pe general cu mersul „revoluției“. Un aspect interesant, semnalat de corespondenții străini: milițienii praghezi care s-au manifestat inițial extrem de violent față de manifestanți au dispărut apoi pur și simplu, lăsând bulevardele în mâna manifestanților. Pentru mulți corespondenți străini, violența inițială neobișnuită a miliției pragheze a avut un caracter provocator, deliberat. În noaptea de 17 noiembrie 1989, generalul Grușko și echipa sa au părăsit Praga, la fel de discret precum apăruseră.

Sofia – complot al nomenclaturii cu binecuvântarea Kremlinului

Prima lovitură pentru Todor Jivkov, aflat la putere de 33 de ani, a venit din partea Turciei, care a suspendat deschiderea graniţei pentru emigranţii turcofoni care părăseau Bulgaria. Imediat au intrat în scenă, devenind şi foarte active, două mişcări ecologiste, „Ecoforum“ şi „Ekoglasnost“, astfel încât, spre sfârşitul lunii august, era vehiculată ideea unei iminente lovituri de palat. În spatele complotului se aflau generalul KGB Sarapov, noul ambasador al Uniunii Sovietice la Sofia, ministrul de externe Petăr Mladenov (n. 22 august 1936 – d. 31 mai 2000) şi Andrei Lukanov (1938, Moscova – 1996, Sofia), ministrul Relaţiilor economice externe. Opoziţia din afara nomenclaturii nu conta însă decât pentru imaginea externă. Todor Jivkov era izolat, fără recunoaştere în relaţiile externe, Bulgaria fiind reprezentată de cei doi complotişti.

„Scrisoarea celor șase“ în varianta bulgară

În Bulgaria, debarcarea lui Todor Jivkov a fost încredințată lui Sarapov, noul ambasador al URSS la Sofia. Anterior, generalul Sarapov deținuse responsabilități însemnate în KGB, fiind și directorul cabinetului lui Andropov.

În 24 octombrie 1989, Petăr Mladenov îi adresează o scrisoare deschisă lui Todor Jivkov, aducându-i, între altele, critici aspre pentru prăbuşirea economiei (n.n. – şi lui Nicolae Ceauşescu i-a fost adresată, în luna martie 1989, o scrisoare deschisă, în care, printre alte grave acuze, i se imputa prăbuşirea economică a României. Nu poate fi chiar o coincidenţă întâmplătoare…). Mladenov şi-a prezentat demisia, dar Jivkov a amânat punerea ei în discuţia Biroului Politic al Partidului Comunist Bulgar.

17.11.1989 – ziua Revoluției de Catifea, declanșată de KGB și considerată de Vaclav Havel drept „un complot pentru abolirea regimului comunist“

Tabăra pro-Gorbaciov a jucat cartea ecologistă

Iniţial, mişcările de stradă au fost timide şi cu participare redusă. Prima demonstrație anticomunistă la Sofia a avut loc pe data de 3 noiembrie 1989. În fapt, circa 5.000 de ecologiști au scandat „Democrație“ și „Transparență“, în drum spre Adunarea populară, unde au înmânat o petiție împotriva realizării proiectului hidroenergetic Rila, considerat dăunător mediului. Acțiunea nu a putut fi oprită, întrucât a coincis cu intensificarea presiunilor externe pentru democratizare.

În istoria oficială, drept început al schimbărilor democratice este menționată data de 10 noiembrie, când, în cadrul unei plenare a Comitetului Central al Partidului Comunist Bulgar, liderii pro-gorbacioviști l-au trimis la pensie, cu mulțumirile de rigoare, pe Todor Jivkov. Acesta începuse să-şi citească imperturbabil raportul, când premierul Atanasov se urcă la tribună pentru a propune retragerea lui Jivkov din funcţiile deţinute şi candidatura lui Mladenov. Ambele propuneri sunt aprobate fără probleme.

Ambasadorul sovietic Sarapov se întâlneşte imediat cu Jivkov, în timp ce Mladenov ia legătura cu Gorbaciov, care-l felicită. Ambasadorul american la Sofia, Sol Polanski (1926-2016), cu o zi înainte, raportase Departamentului de Stat că nu se aşteaptă la niciun fel de schimbări importante la Plenara Comitetului Central din 10 noiembrie, subliniind că „nimeni nu este pregătit să-i arunce o provocare lui Jivkov“. Când semna telegrama redactată de „diplomatul de la CIA“, Biroul Politic, fără participarea lui Jivkov, votase eliminarea acestuia.

Modelul „ex-sovietic“ al tranziției în Bulgaria

Spre deosebire de țările central-europene, în Bulgaria regimul a fost mai puternic, iar presiunile din partea unor grupuri de disidenți – mai slabe. În aceste condiții, rezistența anticomunistă a adoptat forme de luptă ecologiste. Doar după căderea lui Jivkov, la Sofia au început mari demonstrații de stradă și mitinguri, prin care se cerea abrogarea primului articol din Constituție care proclama rolul conducător al Partidului Comunist Bulgar.

Începutul tranziției a urmat modelul fostelor republici sovietice – nu cel al țărilor central-europene. Noul președinte Petăr Mladenov a promis transparență și perestroika. În primii ani tranziția a fost controlată de nomenclatura comunistă, cu ajutorul unor grupări create de securitate. Președintele și liderul partidului, Petăr Mladenov, a fost nevoit să demisioneze după ce a amenințat opoziția cu venirea tancurilor.

În ianuarie 1990, Jivkov a fost pus sub arest la domiciliu. Ulterior, partidul comunist s-a rebotezat ca partid socialist. Tranziția după modelul perestroikist deformează și șterge memoria colectivă despre comunism, care, negat de peste 70% din populaţie în anul 1991, devine dorit de 55% în anul 2007. O posibilă explicație pentru sentimentele pesimiste constă în faptul că în Bulgaria schimbarea a fost dominată de nomenclatura comunistă. Dar Bulgaria nu este nici pe departe un caz singular!

La momentul întâlnirii, M.S. Gorbaciov își îndeplinise în proporție de 75% angajamentul prealabil privind înlăturarea de la putere a ultimilor patru lideri comuniști rămași pe poziții împotriva valului.

Moscova, refuzată de protagoniștii „Primăverii de la Praga“

În Cehoslovacia, ramura locală a KGB-ului din cadrul Securității Statului – STB – a încercat readucerea în actualitate a unora dintre protagoniștii „Primăverii de la Praga“, brutal reprimată de intervenția militară a Forțelor Armate ale tratatului de la Varșovia (fără participarea României). Alexander Dubcek și fostul său ministru Zdenek Mlynar au fost contactați la Viena, dar aceștia, sub amintirea încă vie a evenimentelor din august 1968, refuză orice angajament. Alții însă se vor constitui într-un grup care s-a grăbit să ajungă la Moscova pentru convorbiri cu Mihail Gorbaciov. Acesta îi expediază repede la… KGB! KGB-ul îi pune la dispoziția șefului STB, generalul Alois Lorenc.

Ca și lui Todor Jivkov, şi lui Nicolae Ceauşescu i-a fost adresată, în luna martie 1989, o scrisoare deschisă în care, printre alte grave acuze, i se imputa prăbuşirea economică a României. Nu poate fi chiar o coincidenţă întâmplătoare…

„Turiștii sovietici“ din Cehoslovacia

În preajma zilei de 17 noiembrie 1989, la Praga au sosit, cu câteva avioane, „trupe profesioniste de revoluționari“, adică turiști sovietici din formațiunile „SPETSNAZ“ ale GRU, care s-au amestecat printre demonstranți. Un locotenent al STB, Ludek Zvicak, a fost infiltrat între demonstranți sub identitatea tânărului praghez Martin Smid, în ipostaza de element provocator, care să atace baricadele miliției. A fost împușcat… Vestea morții lui Smid face ocolul lumii, iar mulțimile stârnite nu mai părăsesc străzile. „Turiștii“ sovietici au plecat fără să mai aștepte deznodământul final.

Reporterii occidentali se înființează la domiciliul lui Smid, iar acesta apare acasă viu și nevătămat. Prea târziu însă. Efectul scontat al diversiunii se împlinise. Revoluția învinsese. Un general trimis de Kriucikov, de la Moscova, Viktor Gruskov, generalul Teslenko, șeful antenei KGB de la Praga, și generalul Alois Lorenc au supravegheat întreaga desfășurare a evenimentelor.

„Revoluția de catifea“, declanșată de KGB

Președintele Havel a afirmat categoric că „Revoluția de catifea“ de la Praga, din 17 noiembrie 1989, a fost declanșată de KGB. Havel a definit această operațiune drept „un complot pentru abolirea regimului comunist“, condus de brejnevistul Gustav Husak. Complotiștii, potrivit lui Havel, s-au folosit de protestele studenților pentru a ridica noul regim în șa și pentru a realiza reforma de tip gorbaciovist.

Tot Havel a mai dezvăluit că, inițial, s-a dorit aducerea la putere a unui membru al cabinetului Dubcek (din 1968), aflat în exil la Viena, dar acesta a declinat oferta. Mărturisirea lui Havel de la BBC a fost apoi reluată, în rezumat, și în Die Welt, fiind susținută ulterior și prin alte dovezi.

Generalul Alois Lorenc vizitase anterior Moscova, unde a fost pregătit pentru viitoarele evenimente, iar generalul Viktor Grușko a adus cu sine comandouri Spetznaz ale GRU. Ofițerii Spetznaz, care de la aeroportul Ruzine se împrăștiaseră în toată Praga, conform planului, l-au ținut permanent la curent pe general cu mersul „revoluției“. Un aspect interesant, semnalat de corespondenții străini: milițienii praghezi care s-au manifestat inițial extrem de violent față de manifestanți au dispărut apoi pur și simplu, lăsând bulevardele în mâna manifestanților. Pentru mulți corespondenți străini, violența inițială neobișnuită a miliției pragheze a avut un caracter provocator, deliberat. În noaptea de 17 noiembrie 1989, generalul Grușko și echipa sa au părăsit Praga, la fel de discret precum apăruseră.

Sofia – complot al nomenclaturii cu binecuvântarea Kremlinului

Prima lovitură pentru Todor Jivkov, aflat la putere de 33 de ani, a venit din partea Turciei, care a suspendat deschiderea graniţei pentru emigranţii turcofoni care părăseau Bulgaria. Imediat au intrat în scenă, devenind şi foarte active, două mişcări ecologiste, „Ecoforum“ şi „Ekoglasnost“, astfel încât, spre sfârşitul lunii august, era vehiculată ideea unei iminente lovituri de palat. În spatele complotului se aflau generalul KGB Sarapov, noul ambasador al Uniunii Sovietice la Sofia, ministrul de externe Petăr Mladenov (n. 22 august 1936 – d. 31 mai 2000) şi Andrei Lukanov (1938, Moscova – 1996, Sofia), ministrul Relaţiilor economice externe. Opoziţia din afara nomenclaturii nu conta însă decât pentru imaginea externă. Todor Jivkov era izolat, fără recunoaştere în relaţiile externe, Bulgaria fiind reprezentată de cei doi complotişti.

„Scrisoarea celor șase“ în varianta bulgară

În Bulgaria, debarcarea lui Todor Jivkov a fost încredințată lui Sarapov, noul ambasador al URSS la Sofia. Anterior, generalul Sarapov deținuse responsabilități însemnate în KGB, fiind și directorul cabinetului lui Andropov.

În 24 octombrie 1989, Petăr Mladenov îi adresează o scrisoare deschisă lui Todor Jivkov, aducându-i, între altele, critici aspre pentru prăbuşirea economiei (n.n. – şi lui Nicolae Ceauşescu i-a fost adresată, în luna martie 1989, o scrisoare deschisă, în care, printre alte grave acuze, i se imputa prăbuşirea economică a României. Nu poate fi chiar o coincidenţă întâmplătoare…). Mladenov şi-a prezentat demisia, dar Jivkov a amânat punerea ei în discuţia Biroului Politic al Partidului Comunist Bulgar.

17.11.1989 – ziua Revoluției de Catifea, declanșată de KGB și considerată de Vaclav Havel drept „un complot pentru abolirea regimului comunist“

Tabăra pro-Gorbaciov a jucat cartea ecologistă

Iniţial, mişcările de stradă au fost timide şi cu participare redusă. Prima demonstrație anticomunistă la Sofia a avut loc pe data de 3 noiembrie 1989. În fapt, circa 5.000 de ecologiști au scandat „Democrație“ și „Transparență“, în drum spre Adunarea populară, unde au înmânat o petiție împotriva realizării proiectului hidroenergetic Rila, considerat dăunător mediului. Acțiunea nu a putut fi oprită, întrucât a coincis cu intensificarea presiunilor externe pentru democratizare.

În istoria oficială, drept început al schimbărilor democratice este menționată data de 10 noiembrie, când, în cadrul unei plenare a Comitetului Central al Partidului Comunist Bulgar, liderii pro-gorbacioviști l-au trimis la pensie, cu mulțumirile de rigoare, pe Todor Jivkov. Acesta începuse să-şi citească imperturbabil raportul, când premierul Atanasov se urcă la tribună pentru a propune retragerea lui Jivkov din funcţiile deţinute şi candidatura lui Mladenov. Ambele propuneri sunt aprobate fără probleme.

Ambasadorul sovietic Sarapov se întâlneşte imediat cu Jivkov, în timp ce Mladenov ia legătura cu Gorbaciov, care-l felicită. Ambasadorul american la Sofia, Sol Polanski (1926-2016), cu o zi înainte, raportase Departamentului de Stat că nu se aşteaptă la niciun fel de schimbări importante la Plenara Comitetului Central din 10 noiembrie, subliniind că „nimeni nu este pregătit să-i arunce o provocare lui Jivkov“. Când semna telegrama redactată de „diplomatul de la CIA“, Biroul Politic, fără participarea lui Jivkov, votase eliminarea acestuia.

Modelul „ex-sovietic“ al tranziției în Bulgaria

Spre deosebire de țările central-europene, în Bulgaria regimul a fost mai puternic, iar presiunile din partea unor grupuri de disidenți – mai slabe. În aceste condiții, rezistența anticomunistă a adoptat forme de luptă ecologiste. Doar după căderea lui Jivkov, la Sofia au început mari demonstrații de stradă și mitinguri, prin care se cerea abrogarea primului articol din Constituție care proclama rolul conducător al Partidului Comunist Bulgar.

Începutul tranziției a urmat modelul fostelor republici sovietice – nu cel al țărilor central-europene. Noul președinte Petăr Mladenov a promis transparență și perestroika. În primii ani tranziția a fost controlată de nomenclatura comunistă, cu ajutorul unor grupări create de securitate. Președintele și liderul partidului, Petăr Mladenov, a fost nevoit să demisioneze după ce a amenințat opoziția cu venirea tancurilor.

În ianuarie 1990, Jivkov a fost pus sub arest la domiciliu. Ulterior, partidul comunist s-a rebotezat ca partid socialist. Tranziția după modelul perestroikist deformează și șterge memoria colectivă despre comunism, care, negat de peste 70% din populaţie în anul 1991, devine dorit de 55% în anul 2007. O posibilă explicație pentru sentimentele pesimiste constă în faptul că în Bulgaria schimbarea a fost dominată de nomenclatura comunistă. Dar Bulgaria nu este nici pe departe un caz singular!

Poate incercati sa vedeti aceasta emisiune si, daca veti reusi, veti constata un nivel al discutiilor la care noi nu putem ajunge. Romanul nou nu vrea sa invete nimic, isi doreste doar comfort si prefera spatiile mici. Ca asta inseamna pierderi si situatii care pot deveni periculoase, nu-l intereseaza, in primul rind pentru ca nu le poate percepe ca atare.

Am ajuns o natie lipsita de coloana vertrebrala si ne comportam ca atare. Cine ne-ar respcta si care ar fi motivul?!

Cine este Danile Ganser, unul dintre participantii la discutie:

https://www.danieleganser.ch/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniele_Ganser